Welcome to the opening of “2013D” by Ilja Karilampi, 6 sept 7 pm at our new temporary space at Karl Johansgatan 152. More info soon.

|

|

|

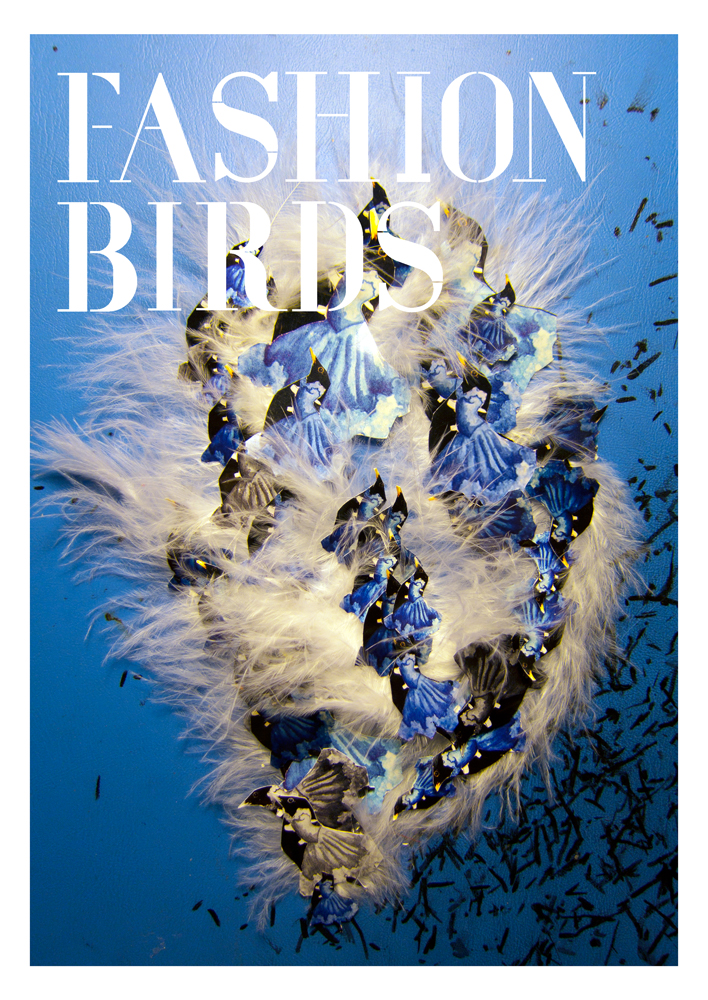

Book Launch 29 April, 7-9 pm at Nextart Gallery & Bookshop

Participating artists: Cora Hillebrand Welcome!

|

|

Interview with Marcus Hansson

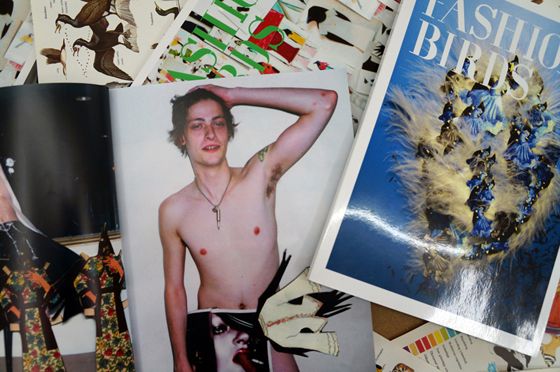

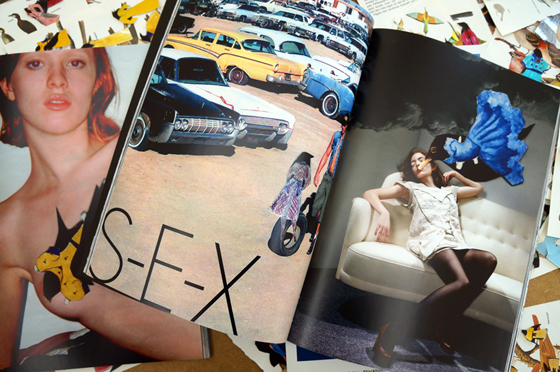

How did you get the idea to create “Fashion Birds” and when did it start? I worked with black birds. I did not know what species they belonged to, but for some reason I looked for them online and printed them out … in big quantities. I created installations with birds that did not lead to anything concrete. Later I found all these clothes that the birds are now wearing (my partner and a friend made clothes for paper dolls in the 70′s and they were about to be thrown away). The work has been an on-going project for several years. The birds have almost ceased to be birds with clothes on and become a new material, a mass, a mix between color and form. What is it about fashion that interests you? May I say everything? I don’t know if it is fashion in itself that interests me (yes, sometimes, maybe). Sometimes it’s beautiful, and sometimes I think that I would like to be a part of the fashion world. I cling and tap on. The birds are my ticket to this world. Fashion is so concrete: off/on and now/then. And then I arrive with my silly little paper-doll dressed birds and want to be a part of it, sort of. You often appropriate other people’s images. What attracts you to do this? And why do you think there is still such an opposition, an outrage, against this act? Yes it is true, often actually. I have made my own photo albums with text on Polaroids and everything was from the TV. In Joyspreader I collected all the images that had anything to do with nature and they came from different directions, it was maybe 20,000 images. Before “Fashion Birds” I shot scenes from the news on the Internet (” Souvenir “) and made them into paintings. I think I add something to the images or destroy them. I really see them as my own. Agitation has varied.”Fashion Birds” (the fashion magazines) is probably the work that people have asked most about, and if you can do something like that. When and why did you choose to not work with more traditional photographic methods, and instead incorporate collage, textile, etc.? This a continuation of the last the question. I got into photography as a street photographer, and even as such, I think you are stealing pictures (I took pictures of people on the street and often they didn’t notice that I was photographing them). I saw it as my own work, just like today. Then I measured mostly my days in how many pictures I had taken. I think I was good at “taking pictures”, but then after a long journey and a lot of photography, when I was about to develop the images, I put maybe 40 pieces of film rolls in fixative first, instead of putting them in the developing liquid. And then I decided that I probably should change my way to work. Maybe it’s time to change my work now again, when I measure my days in how many birds I have cut. How does “Fashion Birds” differ from your previous works? The rich amount and the many repetitions can be found in almost all of my previous work, but perhaps “Fashion Birds” is more about color and form. Something I have had a difficulty facing before. I have thought of ease. And so for the exhibition at Nextart I thought that the art on the walls would be a kind of decoration and promotion to the fashion magazines.

|

|

|

|

Interview with Ryan L. Moule In your new photo-series, which is presented in the exhibition “Latency Principles” at Nextart Gallery, you have left the photographs chemically unfixed. Why? And what kind of impact does this working-method have on the images? Both bodies of work exhibited at Nextart form a question in relation to complex processes of forgetting. The unfixed surface of these photographic prints act silently initially, we don’t see the eroding process in the same way as the video documentation of ‘January 1988’. The hidden quality of this slower process is something that can be overlooked. I like that the first reading of the images can be changed once the viewer is informed of the process (or when revisiting the exhibition they see a physical change in the prints surface). I think this second hidden reading of an image is the thing that i’m most drawn to when thinking about the re-presentation of any given event. Within the act of forgetting there is an oscillation between this first and second reading. For instance, the first layer of forgetting is knowing we’ve forgotten something, like someone’s name or a place. We know we know it but we can’t quite access it. The second layer of forgetting on the other hand is what we don’t know we’ve forgotten. Its this realisation of an unknown, unknown that all my works look towards. The rooms photographed both physically balance between appearance and disappearance (insofar as they are on the edges of the land, about to fall into the sea) but also for me they act as a psychological spaces, like chambers of the mind that perhaps cannot be accessed but only glimpsed. I find this reappearance and disappearance of ‘trace’ both uncomfortable and deeply melancholic. Perhaps its best understood as the image of an outline when you close your eyes. It presents itself unfixable. In “January 1988″ the photo of you and your mother is slowly blurred in water. It’s like a reverse developing-process, where you dissolve the photo instead of preserving it. Do you remember when and how you got this idea? And was it a painful procedure? It was a very organic process, born from a personal response to the contemporary condition of the image. In a time in which medium is ubiquitous, the referent seemed to me to be hollowed of any inherent meaning. Throwaway, superficial almost. Flicking through images from my family archive an image of my mother (younger than I am now) and me as a baby, arrested my attention. The first reading of the image personal, but its second reading became far more troubling. The fear that this image, an image that represents not just surface, but something far more complex, could, after my time be something throwaway, something superficial, something entirely hollowed of inherent meaning was something too intense to ignore. I began to think of the chemical make up of the image and how its apparent stillness could be pushed to its limits. Its a simple action that once initiated is undoable. The role of the one-off sculptural work in which the original image is erased in front of a live audience acts in some way to reference the way memory is constructed. Witnessing the actual erasure within a live situation has a different reading to the presentation of the video documentation of this work. Our relationship to technology and the ability to recall lost information is something that has changed the way we need to remember. This prosthetic memory that technology enables us to have at our disposal, being able to recall almost anything through a search engine or database, I think questions the ability to forget anything. This question of total recall is almost as frightening as total loss. What are you working on at the moment? I’m still developing the photographic works which are on show at Nextart. Its very fresh work (made in early 2013) so still have lots of negatives to look at. I’ve also been making a crystal chemical which is made of salts. It looks like ice but unlike ice, this substance remains solid at room temperature. This work is being made as a commission for a new site specific work for ‘Waddesdon Manor’ in Buckinghamshire, England. The work is set to be complete by the end of the summer months so lots of experimentation will begin shortly. I also have my final show at the Royal College of Art which i’m slowly working toward. I’m going to be in the dark room for the next two months making very large and very black photographic prints. Fun times!

|

|

|

Interview with Karin Dolk Your works often incorporate sound and language. When did this interest start? And how has this affected your daily life? My work deals with certain aspects of language as a means of examining identity and social representation. I work mainly with video and sound because I’m interested in its relationship to time and performativity, and often find sound more suggestive than image, more difficult to pin down. Music has always been very important to me, but I pay more and more attention to all kinds of everyday sounds: cultural sound, language sound, non-verbal sound, subtle sound, noise… In your video pieces “A sad song” and “Words wound” repetition is a common theme. Which are your philosophical thoughts on this subject matter? Repetition implies the impossibility of repetition. What seems the same always contains a difference, a variation. However, patterns and roles in society tend to be repeated ad infinitum. I’m concerned with examining the structural and social components of repetition. The parrot in “Words wound” repeats some words learned by rote, but most of his speech are phrases, words and sounds that create a – not always flattering – portrait of his surroundings, and in some way empower him. The repetition in “A sad song” is related to the musical structure of Karelian laments, as well as to ideas of resilience and contemplation. Tell us a bit about “[əˈnʌðə]” that is presented at Nextart Gallery at the moment. “[əˈnʌðə]” is a silent sound film, a script made solely for Foley – the sound effects produced live by a Foley artist in the post-production of movies. The project originated from a previous project I made about film dubbing. As many of my other works, it’s related to ideas of translation, de-contextualization and meta fiction. The sound in the film suggests several possible film stories that could exist somewhere. However, when looking at the actual action in the film, another story appears. The title, as well as the accompanying phonetic sound script on the walls, is connected both to the idea of sound in language and the insufficiency of language – and in a way again to a meta layer, due of the impossibility of translating a real sound to onomatopoeia and then to writing. The title also refers to being one more/different in relation to the possible “original” films and the one/fragmented body of the person that dub all the sounds and characters. Does [əˈnʌðə] differ from your earlier work? And if yes – how? “[əˈnʌðə]” connects in many ways with my earlier work. However, it’s the first time I’ve written and worked with a script, particularly a real “sound script”. I also feel it has a very clear connection to Scandinavian cinema: the materials, objects, the mise en scène…

|

|

© 2014 Nextart Gallery & Editions / Contact us